The Bradford Halloween Peppermints Contaminated with Poison

A small quantity of sweets is as closely associated with Halloween as a eerie costume or a menacing pumpkin. However, on the 31st of October in 1858, this typically innocent delight claimed the lives of multiple children, instigating widespread panic throughout Bradford and a swiftly mounting death toll. This is the account of how a mix-up at a pharmacy, centred on an attempt to economise a few pennies on sugar, profoundly shook Victorian Britain and led to alterations in UK legislation.

When William Hardacre closed up his stall that day, he surely patted himself on the back for a successful day’s trading.

The market vendor, known to many as Humbug Billy, had not only managed to sell five pounds of peppermint lozenges to the people of Bradford, but he’d also negotiated a bargain price to start with.

Upon collecting the sweets from the wholesaler, he noticed they were darker than usual. This prompted him to haggle with confectioner Joseph Neal, resulting in a saving of half a penny per pound.

However, Hardacre’s failure to question the quality of the sweets would prove to be a costly mistake. By nightfall the next day, several of his customers had met their demise.

Initially, the doctor who attended to nine-year-old Elijah Wright in the early hours of Halloween in 1858 believed the boy had succumbed to cholera.

Surgeon John Roberts thought the symptoms – vomiting and convulsions – were consistent with the disease, which was rampant in England at the time.

An hour later, Joseph Scott’s father left their home on Railroad Street to fetch a doctor for his 14-year-old son, who had suddenly fallen violently ill. By the time he returned, it was too late.

Both, it later emerged, had purchased sweets from Humbug Billy the day before – though the connection had not yet been established.

It was Dr. John Henry Bell who suspected the sweets when he arrived at Jowett Street at about 3 pm.

Urgent Warnings

Orlando Burran, aged five, and his three-year-old brother, John Henry, lay lifeless before him; their father had been unwell that morning, and two others in the house were also ailing. All of them had consumed the sweets. The doctor sent a sample to chemist Felix Marsh Rimmington for testing.

As the day progressed, reports flooded in from all over the district of people falling ill and passing away. Upon learning about the sweets from the Burrans, the police visited Hardacre’s residence. They discovered that he was not only bedridden from consuming his tainted wares, but he had also sold about 1,000 sweets the day before.

“The police were horrified to discover that there were [so many] sweets in circulation,” remarks Dr. Lauren Padgett, assistant curator of collections at Bradford District Museums and Galleries. “At this point, it was getting late into Sunday evening, so they took to the streets, ringing bells to get people’s attention and shouting warnings. They went from pub to pub, telling people ‘do not eat the sweets, they’re poison’.”

Cautionary notices were promptly printed and displayed in public areas.

In the Bradford Observer, a list was published, enumerating those who had succumbed to the poison or were gravely unwell. By the 4th of November, the grim toll had risen to 18, with the youngest victim being a mere 17 months old. The newspaper described this escalating catalogue of casualties as “the most dreadful calamity that perhaps ever befell the district… [spreading] suffering, mourning and woe.”

Detectives swiftly pieced together the chain of events leading to the adulteration of the sweets.

They traced the path from Hardacre to Neal, who believed he had substituted some of the expensive sugar with plaster of Paris, a practice common in the 19th Century. This powder, often referred to as “daft,” was used as a cost-effective alternative to pricey ingredients and could be procured inexpensively from pharmacies.

Unbeknownst to Neal, on the day he dispatched his colleague to retrieve the daft, the druggist Charles Hodgson was unwell and had simply directed his untrained apprentice, William Goddard, to its location. Unfortunately, the room contained two unmarked casks of white powder – one holding the benign daft, the other the deadly arsenic.

“Goddard went to a barrel he assumed contained plaster of Paris and collected 12lbs of it, gave it to the young lad who took it back to the confectioner’s, where another employee began to make the lozenges and mixed it in,” explains Dr Padgett.

“He himself became really unwell from being exposed to the arsenic but rather than alarm bells going off, he carried on making them.”

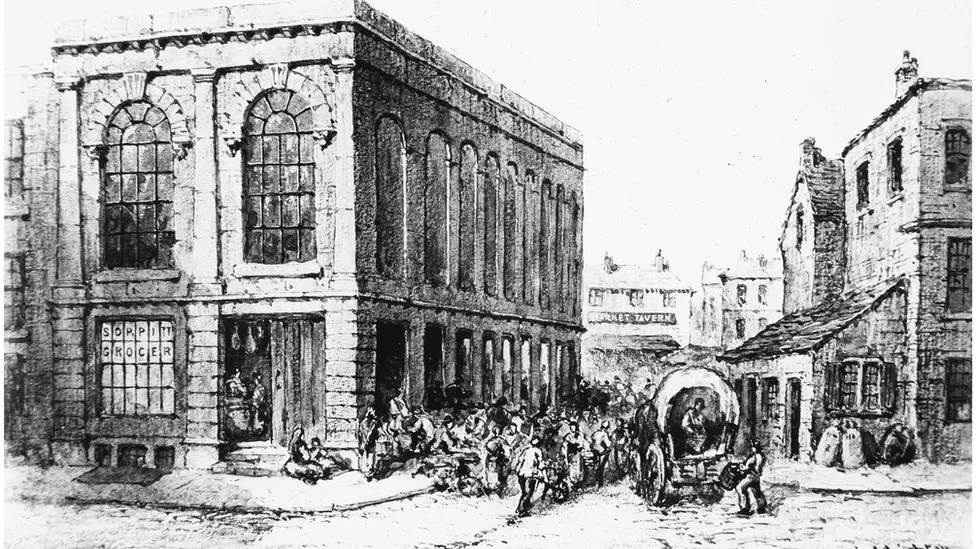

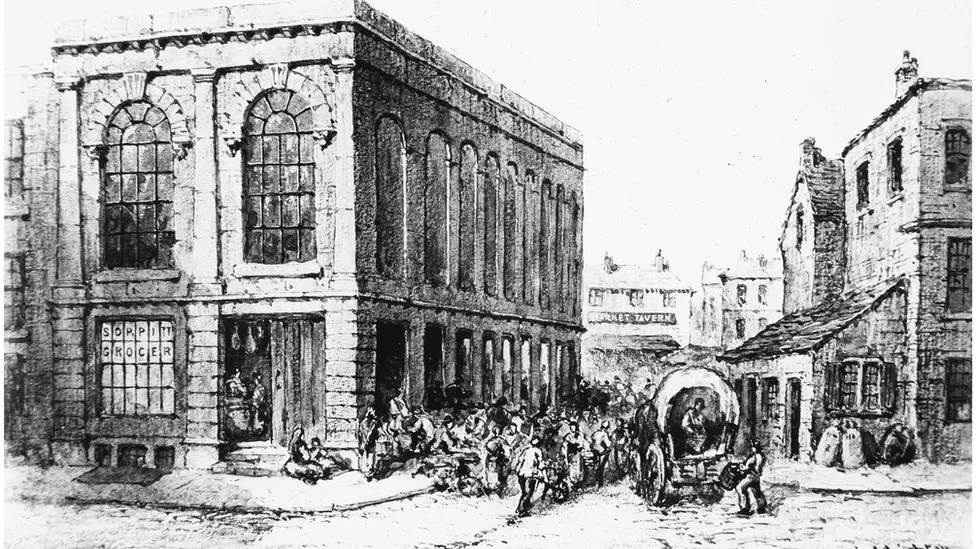

The calamitous sequence of events continued as Humbug Billy collected his order and shrewdly negotiated a reduced price for the peculiar-looking sweets, subsequently peddling them at his stall in Green Market, later known as Rawson Market.

Upon analysis by chemist Rimmington, he informed the inquest that he had discovered “an abundance of arsenic – in quantities sufficient to be lethal”.

In a single lozenge, he detected 16 grains of arsenic – four times the amount deemed a lethal dose, more than enough to cause multiple fatalities.

“Spectacular is the amount of arsenic,” remarks sweets and confectionery historian Alex Hutchinson.

“To us, as 21st Century consumers, it seems absurd that this incredibly poisonous substance, devoid of odour, tasteless, stored in an unmarked barrel beside unlabeled items, could be handed over the counter to anyone.”

‘Heart-wrenching for all’

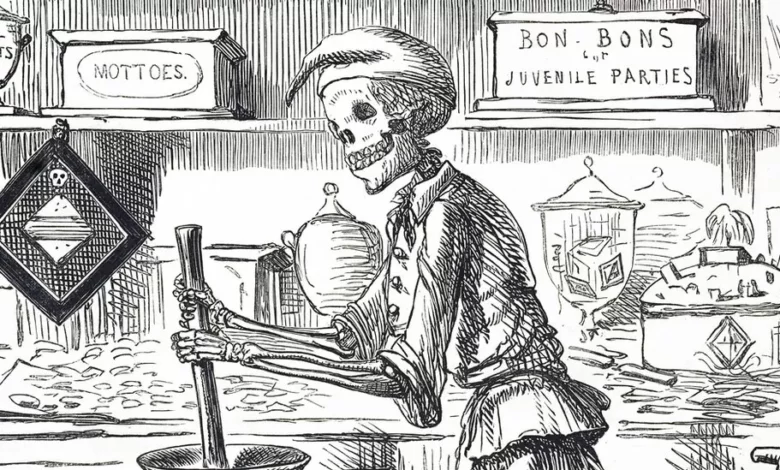

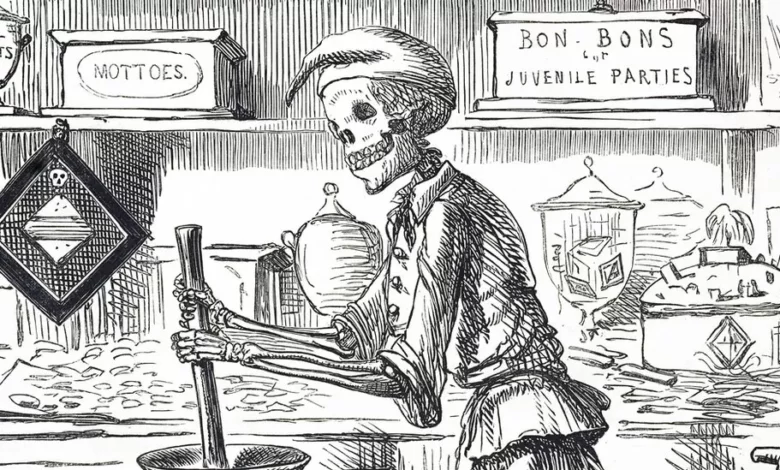

The poisonings triggered a public outcry, with newspapers nationwide extensively covering the case. Artist John Leech, known for his illustrations in Punch magazine, became as renowned for his depiction of a skeleton grinding sugar in a sweet shop as he was for illustrating the first edition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

However, the suffering was most keenly felt in Bradford – now a city, but then a town of 50,000 inhabitants – where “for a brief period, [it was] as if a dreadful plague had smitten us”, penned the Bradford Observer.

Officially, 20 people – many of them children – lost their lives, and a further 200 individuals fell seriously ill. Yet, Dr. Padgett suspects the actual figures were likely much higher, as the tainted sweets were discovered as far afield as Leeds and Bolton.

“It had been deeply distressing for everyone,” she reflects. “Bradford was a tightly-knit community, so when something occurred within the community, everyone felt its impact, which is precisely what transpired in this instance. It’s probable that people knew someone who had been affected.”

Ultimately, the Bradford poisonings underscored the crucial need for safeguarding the safety of medicines and consumer products, according to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

This led to the enactment of the Pharmacy Act of 1868, which not only restricted the sale of poisons and dangerous drugs to qualified pharmacists and druggists, but also established a regulatory framework for the sale of poisons that persists to this day, mandating appropriate labelling for drugs.

Had it been in place a decade earlier, it might have prevented Goddard from mistakenly selecting the wrong barrel and selling the powder. However, it wouldn’t have addressed the broader issue of adulterated foods – the industry required regulation and reform, asserts Ms. Hutchinson.

“Until 1820, most of us lived in villages or small towns where we knew the individuals providing our food. But with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, manufacturers began producing items in large quantities, adding substances to dilute the food either to prolong its shelf life, enhance its appearance, or reduce costs. And that was the predicament in Bradford.”

A law prohibiting unadvertised adulteration was eventually passed in 1875 through The Sale of Food and Drugs Act. However, warnings could have been heeded much earlier, notes Ms. Hutchinson. In 1820, chemist Friedrich Accum wrote in his book “Death in the Pot” that common foods like milk, flour, beer, and sweets were routinely tampered with.

“Accum’s book was a tremendous bestseller – he cautioned consumers to be vigilant, and they began to realize that there were adulterants in their food,” she asserts. “But there simply wasn’t the legislation to protect people, and I believe Bradford was somewhat the final straw.”

Although laws were established to prevent a tragedy like Bradford from recurring, it’s perhaps startling to learn that no one faced criminal charges.

Humbug Billy was never apprehended but suffered paralysis from the effects of consuming his contaminated sweets. Neal, Goddard, and Hodgson were all detained for manslaughter, and the inquest determined the latter was culpable, although it conceded that “the arsenic had been sold accidentally and mixed under the assumption that it was innocuous.”

The York Assizes did not reach the same conclusion, and all three were ultimately acquitted in December 1858. The grand jury dismissed the charges against Neal and Goddard, and according to the Bradford Observer, the judge himself halted the prosecution against Hodgson.

“No other outcome could have been expected,” the court report read. “The only truly criminal aspect in the entire affair was what the law could not address – the practice of adulteration, and the supply of ‘innocuous’ for that purpose. If this calamity imparts this lesson, it will not have been in vain.”

In the end, the chain of events leading to the Bradford poisonings was characterized by “pure incompetence,” adds Ms. Hutchinson. “But as a Halloween tale, it’s rather a macabre one.”